DO AND SMT

HANDBOOK

A GUIDE FOR DESIGNATED

OFFICIALS FOR SECURITY AND

SECURITY MANAGEMENT TEAMS

New Edition

Department

of Safety

and Security

2

Security for the United Nations, for a better world.

VISION

To enable United Nations system operations through

trusted security leadership and solutions.

MISSION

3

DO AND SMT

HANDBOOK

This handbook is provided exclusively for the use

of authorized United Nations personnel. It may not

be copied or reproduced by any means, manual,

electronic, photographic or photostatic, neither

may it be disassembled without the express written

permission of the United Nations Department

of Safety and Security (UNDSS). Copyright

with respect to all parts of this handbook and

attachments, including the name and logo of the

United Nations, remain the property of the United

Nations and may not, in whole or in part, be used

or referred to by any other person or organization

without express written permission from UNDSS.

This handbook will be revised and updated on

a regular basis. Feedback and comments are

therefore welcome, and should be sent to undss.

4

5

ABBREVIATIONS

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

UNSMS & IASMN MEMBERS

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

THE UNITED NATIONS SECURITY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

SECURITY POLICY FRAMEWORK

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTIONS AND FRAMEWORK

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

SECURITY ARCHITECTURE IN-COUNTRY

SECURITY RISK MANAGEMENT

SPECIFIC SRM MEASURES

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

UN-WIDE CRISIS MANAGEMENT

SAFETY AND SECURITY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

CRISIS PREPAREDNESS

INCIDENTS TARGETING PERSONNEL AND PREMISES

SPECIFIC SECURITY CONSIDERATIONS

GENDER AND INCLUSIVITY

LOCALLY RECRUITED PERSONNEL

ABDUCTION OF PERSONNEL

ARREST AND DETENTION OF PERSONNEL

PHYSICAL SECURITY

EVENT SECURITY

PROTECTIVE SECURITY SERVICES

CBRN

PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT

SECURITY OF IMPLEMENTING PARTNER NGOS

SECURITY COMMUNICATIONS

SAFETY

SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

SECURITY BUDGETS

DUTY STATION CLASSIFICATION

DANGER PAY

ROLE OF SENIOR UNDSS REPRESENTATIVE

UNDSS ORGANIZATION CHART

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

16

17

19

20

27

33

37

38

41

46

48

50

51

52

53

54

56

57

58

58

60

61

61

62

66

67

70

71

72

74

6

ASC

ASMT

BOI

CATSU

CBRN

CISMU

CMT

CMWG

CSA

DO

DOS

DPO

DPPA

DRO

HLCM

IASMN

ICSC

IIH

JFA

JOC

LCSSB

OCB

OSH

P/C/SA

PC

PSA

SA

SFP

SIOC

SOP

SMT

SRM

SSAFE

TRIP

UNCT

UNSMIN

UNSMS

ABBREVIATIONS

Area Security Coordinator

Area Security Management Team

Board of Inquiry

Commercial Air Travel Safety Unit (of UNDSS)

Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear

Critical Incident Stress Management Unit (of UNDSS)

Crisis Management Team

Crisis Management Working Group

Chief Security Adviser

Designated Ocial

Department of Operational Support

Department of Peace Operations

Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs

Division of Regional Operations (of UNDSS)

High Level Committee on Management

Inter-Agency Security Management Network

International Civil Service Commission

Integrated Information Hub

Jointly Financed Activities

Joint Operations Centre

Locally Cost-Shared Security Budget

Operations Coordination Body

Occupational Safety and Health

Senior UNDSS representative (either a PSA, CSA or SA)

Programme Criticality

Principal Security Adviser

Security Adviser

Security Focal Point

Security Information and Operations Centre

Standard Operating Procedure

Security Management Team

Security Risk Management

Safe and Secure Approaches in Field Environments (training)

Travel Request Information Process

United Nations Country Team

United Nations Security Management Information Network

United Nations Security Management System

7

W

elcome to the DO and SMT

Handbook: A Guide for

Designated Ocials for

Security and Security Management

Teams. This Handbook is a convenient

reference to the policy and security

management framework provided

by the United Nations Security

Management System (UNSMS).

As Designated Ocials for Security and members of Security

Management Teams (SMTs), your roles are critical to the effective

management of the UNSMS. We rely on your leadership to enable

the safe and secure delivery of programmes for all UNSMS entities

in your Designated Area. We also depend on your judgement

and understanding to make critical decisions, often under

pressure and in sharply evolving contexts. To help you in this

role, you will be guided by your security experts in-country and

at headquarters, and through specialized trainings and products

such as this one. I am also ready to assist you in this crucial role

and welcome the chance to hear your concerns and challenges.

As the work of the United Nations has become increasingly fraught,

with personnel and operations an enduring target of violence, we

must work together to ensure we are prepared to meet safety and

security challenges head on. Through collaboration, communication

and an orientation towards practical solutions, we will strive to

enable the delivery of United Nations mandates and programmes.

UNDSS, and the wider UNSMS, stand ready to guide and support you.

Mr. Gilles Michaud

Under-Secretary-General for Safety and Security

September 2020

FOREWORD

8

T

his Handbook covers the main policies and procedures that

govern the United Nations Security Management System

(UNSMS). These policies are contained in the UNSMS Security

Policy Manual (“blue book”) and are complemented by detailed

guidelines compiled in the Security Management Operations

Manual (“red book”) and other specialized manuals. These are

made available through the United Nations Security Management

Information Network (UNSMIN) at www.unsmin.org, via the library

tab (sign-in credentials are obtained through UNDSS.)

UNSMS security professionals in the Designated Area will serve as

the best resource to support your security management functions.

UNDSS Headquarters offers further support through its specialized

functions. Finally, the USG UNDSS, as the principal adviser on safety

and security to the Secretary-General, stands ready to provide

leadership support and advice.

INTRODUCTION

9

ADB Asian Development Bank CTBTO Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-

Ban Treaty Organization DESA Department of Economic and Social

Affairs DOS Department of Operational Support DPO Department of

Peace Operations DPPA Department of Political and Peacebuilding

Affairs EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization IAEA International Atomic

Energy Agency ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization ICC

International Criminal Court ICJ International Court of Justice IFAD

International Fund for Agricultural Development ILO International

Labour Organization IMF International Monetary Fund IMO

International Maritime Organization IOM International Organization

for Migration IRMCT International Residual Mechanism for Criminal

Tribunals ISA International Seabed Authority ITC International

Trade Centre ITU International Telecommunication Union OCHA

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs OHCHR Office

of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights OPCW

Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons PAHO

Pan American Health Organization UNAIDS Joint United Nations

Programme on HIV/AIDS UNCTAD United Nations Conference

on Trade and Development UNDP United Nations Development

Programme UNDSS United Nations Department of Safety and

Security UNEP United Nations Environment Programme UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund UN-Habitat United Nations

Human Settlements Programme UNHCR Office of the United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICC United Nations

International Computing Center UNICEF United Nations Children’s

Fund UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Organization

UNOCT United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism UNODC United

Nations Office on Drugs and Crime UNOPS United Nations Office

for Project Services UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works

Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East UNU United Nations

University UNV United Nations Volunteers UN Women United

Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women

UNWTO United Nations World Tourism Organization UPU Universal

Postal Union WBG World Bank Group WFP World Food Programme

WHO World Health Organization WIPO World Intellectual Property

Organization WMO World Meteorological Organization WTO World

Trade Organization

UNSMS & IASMN Members

LEGAL & POLICY

FRAMEWORK

1

11

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Safety and Security Roles and Responsibilities in HQ

I

n the discharge of your security management duties, there are

a number of legal and policy documents with which you must

be familiar. These provide the framework to guide key decisions

impacting the safety and security of United Nations personnel.

THE UNITED NATIONS SECURITY

MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

The UNSMS is composed of all United Nations system organizations

and other international organizations that have signed a Memorandum

of Understanding with the UNSMS for the purposes of safety and

security. The UNSMS has over 50 member organizations and is led

by UNDSS under the executive authority of the USG UNDSS.

There are currently four international organizations that have signed

a Memorandum of Understanding with the United Nations for the

purposes of safety and security: Asian Development Bank, European

Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Criminal

Court and the International Organization for Migration.

Secretary-General

• Overall safety and security of UN personnel in HQ and eld

• Accountable to Member States

USG UNDSS

• Executive direction

• Overall responsibility for safety and security of UN personnel

at HQ and eld

• Accountable to the Secretary-General

• Chairs the IASMN

Executive Heads of UN Organizations

• Accountable to the Secretary-General

• Ensure the goals of UNSMS are met within their organization

12

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

There are four essential policies with which any security decision

maker in the United Nations system should be familiar.

1. The Framework of Accountability for the UNSMS stipulates

that the DO is accountable to the Secretary-General, through the

USG UNDSS, and is responsible for the safety and security of United

Nations personnel, premises and assets in the Designated Area.

The Secretary-General delegates to the DO the requisite authority

to take decisions, subject to review of the USG UNDSS. The SMT,

chaired by the DO, advises the DO on all security-related matters.

These responsibilities are addressed in more detail in the following

chapters.

2. The Policy on Applicability for the UNSMS identies which

individuals fall under the scope of the UNSMS and are therefore

covered by United Nations security arrangements. They include

internationally and locally recruited personnel and their eligible

family members, interns, United Nations Volunteers and, generally,

consultants for United Nations entities. In practical terms, this

means that any individual who has signed a direct contractual

agreement with one of the UNSMS organizations falls under the

UNSMS.

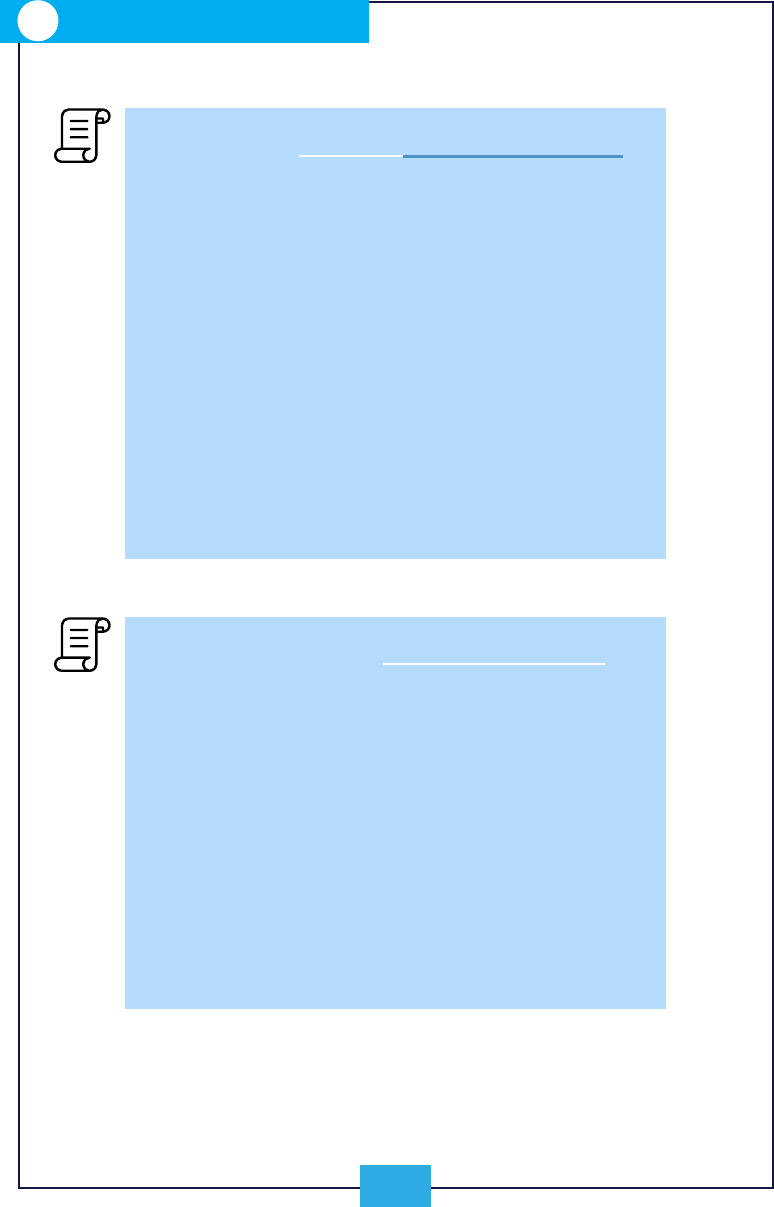

UNDSS was established on 1 January 2005 pursuant to

General Assembly resolution A/RES/59/276, with a view

to unifying the disparate security components of the

existing Oce of the United Nations Security Coordinator

(known as UNSECOORD) and the Security and Safety

Services, including those in the regional commissions.

UNDSS manages a network of security advisers, analysts,

ocers and coordinators in more than 100 countries in

support of around 180,000 United Nations personnel,

400,000 dependants and 4,500 United Nations premises

worldwide.

Establishment of UNDSS

13

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

In missions led by the Department of Peace Operations (DPO) or the

Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), police

and military personnel who are deployed individually all fall under

the UNSMS (i.e., contingent members are excluded), although their

family members are excluded.

Individuals recruited locally and paid by the hour are excluded from

this policy.

3. The Policy on Security Risk Management (SRM) outlines

the concept and principles which guide all decisions related to

security within the UNSMS. The SRM process is a structured and

risk-based decision-making tool. It guides the process to enable

programme delivery through the identication and assessment

of the threats to United Nations personnel, assets and operations

in a Designated Area, and assists in the identication of security

measures and procedures to reduce vulnerability and the level of

associated risk. This process supports the dicult risk decisions

the DO must take, in collaboration with the SMT, in regards to the

safety and security of United Nations personnel, including what

risks are deemed acceptable. The SRM is explained in detail on

page 27.

4. The Programme Criticality Framework is a system-wide

policy endorsed by the High-Level Committee on Management and

the Secretary-General’s Policy Executive Committee. The aim of

the Programme Criticality Framework is to assess programmatic

priorities in changing or volatile security situations to allow

decisions on acceptable risk. This decision is made by balancing the

“residual risk” of a programme against its assessed criticality. The

responsibility for Programme Criticality assessments lies with the

senior United Nations representative in-country (i.e., the Resident

Coordinator or Special Representative of the Secretary-General). Its

application is mandatory in environments of high or very high security

risk. However, assessments are also recommended as preparatory

measures in those countries with unpredictable or rapidly changing

security environments: such proactive assessments can facilitate

rapid decision-making if the security risks are suddenly elevated.

(Please see www.programmecriticality.org for more information.)

14

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

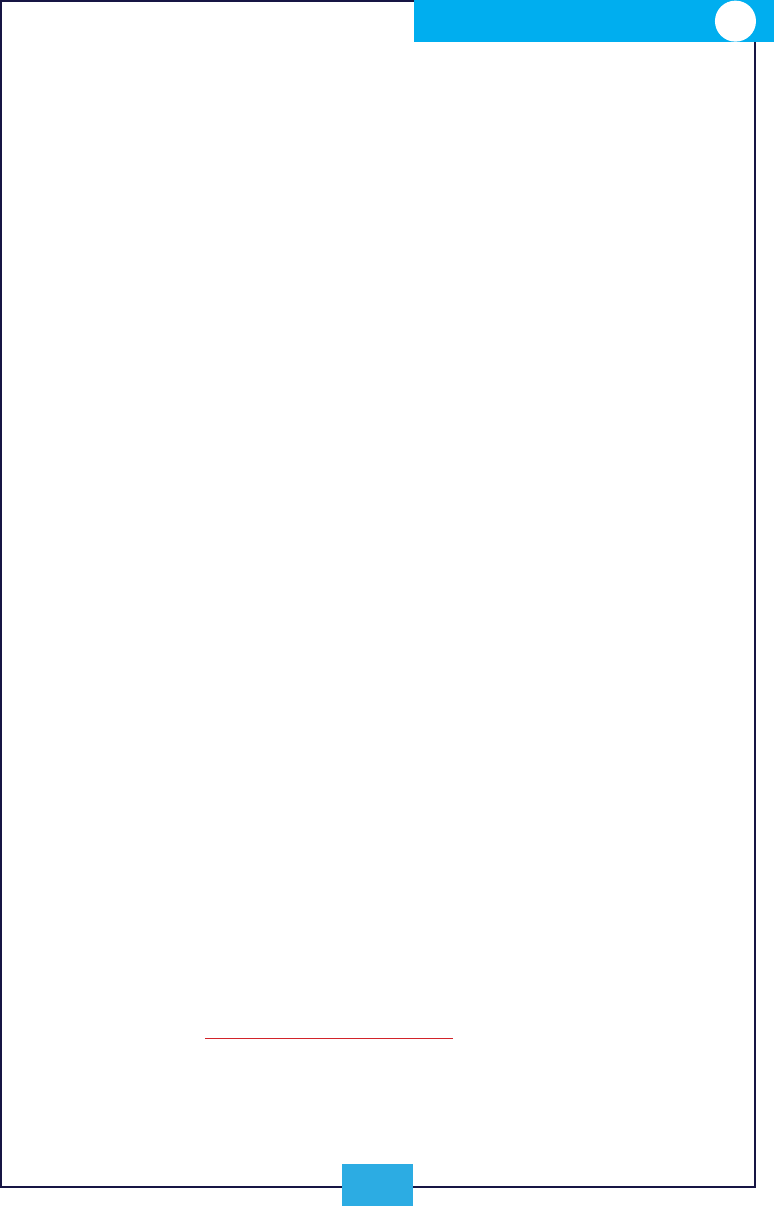

Unacceptable

Very High

High

Medium

Low

N/A

PC1

PC2

PC3

PC4

- Life-saving activities (at scale)

- Any activity endorsed by the SG

Two rating Criteria

- Contribution to each in-country

UN strategic result

- Likelihood of implementation

Residual Risk

Programme Criticality Level

SRM Process

Acceptable Risk Model (PC)

IMPACT

LIKELIHOOD

NEGLIGIBLE MINOR MODERATE SEVERE CRITICAL

VERY LIKELY Low Medium High Very High Unacceptable

LIKELY Low Medium High High Very High

MODERATELY

LIKELY

Low Low Medium High High

UNLIKELY Low Low Low Medium Medium

VERY

UNLIKELY

Low Low Low Low Low

Fig. 1: The UNSMS Acceptable Risk Model compares Residual Risk and Programme

Criticality levels.

15

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

HLCM

High Level Committee on

Management

IASMN

Working Groups

IASMN

Steering Group

IASMN

Inter-Agency Security

Management Network

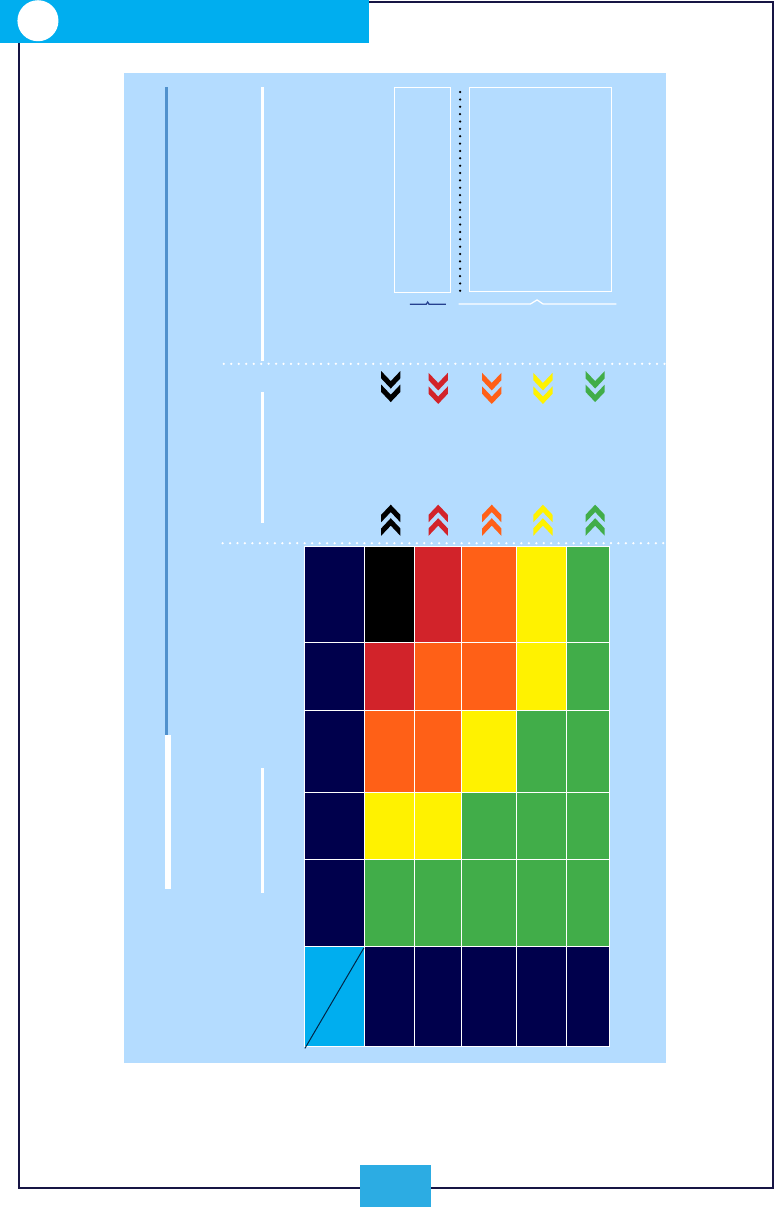

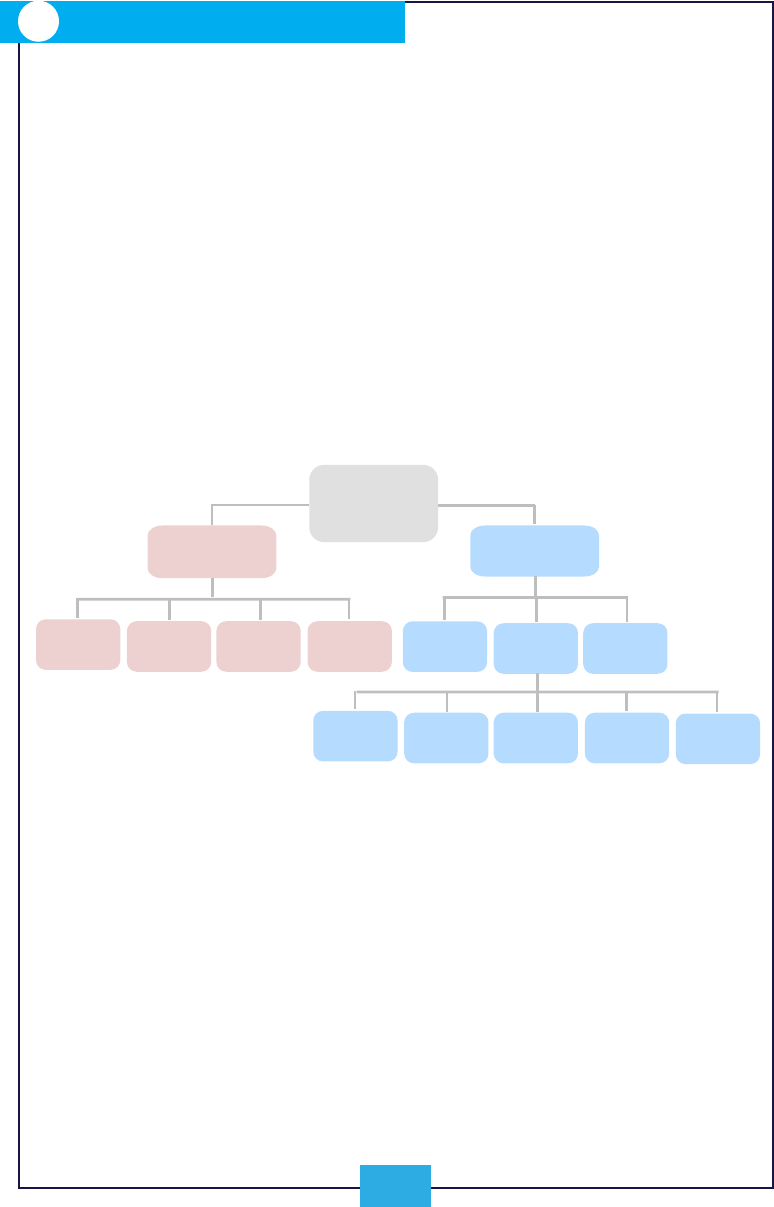

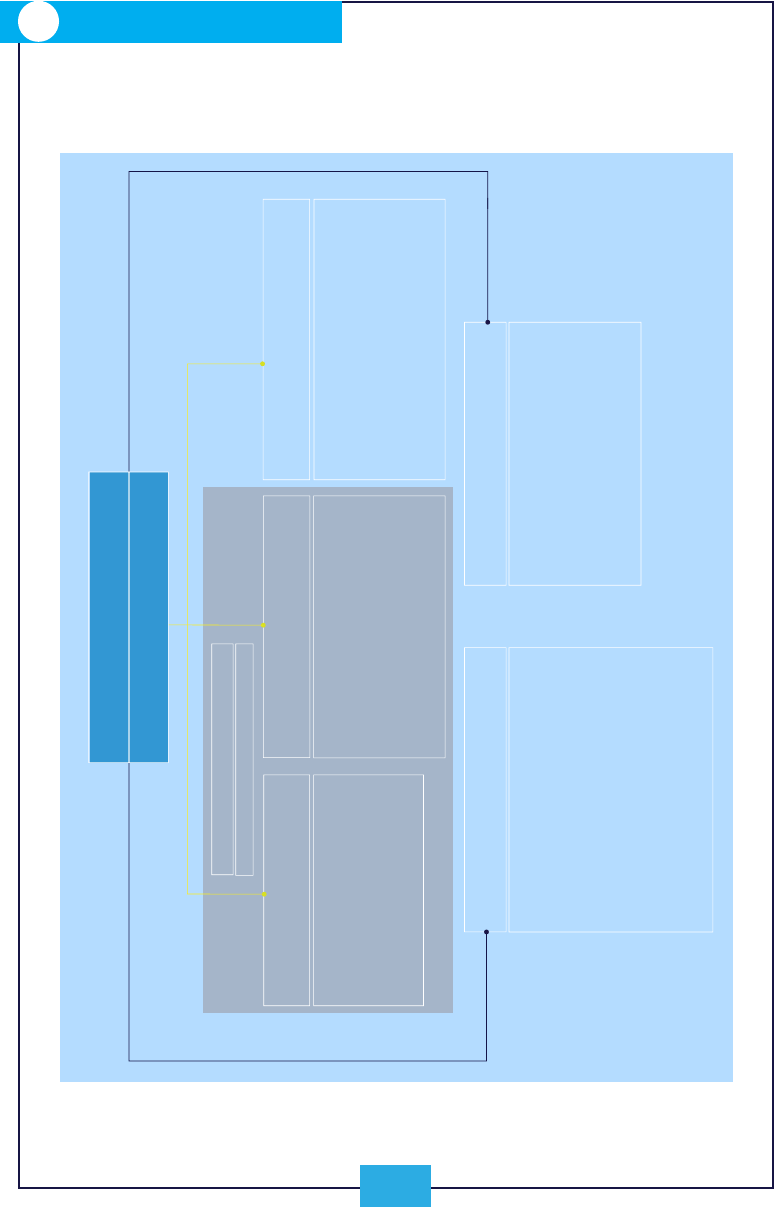

UNSMS Policy-Making & the IASMN

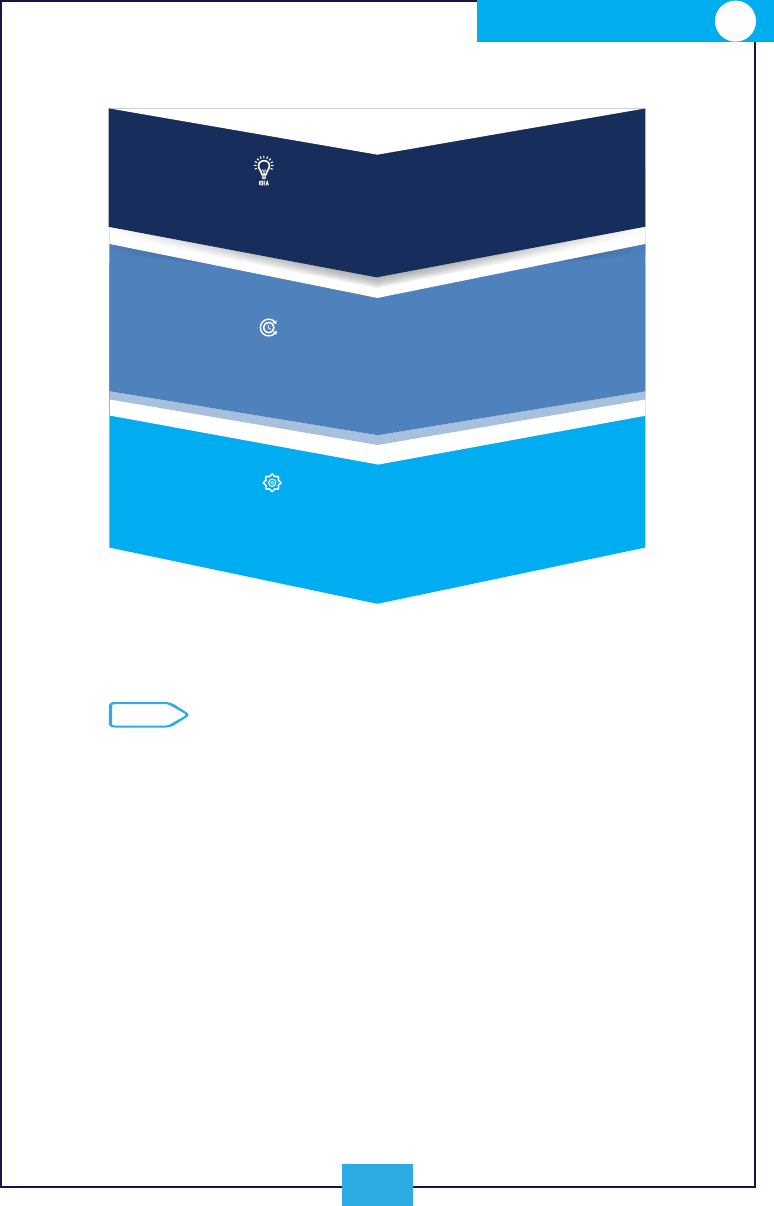

Security management policies within the UNSMS are

initiated, developed and reviewed by the Inter-Agency

Security Management Network (IASMN), a specialized

network chaired by the USG UNDSS and composed of the

senior security managers of all UNSMS organizations.

The IASMN meets twice a year and is supported by a

Steering Group and thematic working groups. The

IASMN falls under the auspices of the High-Level

Committee on Management, one of three pillars of the

Chief Executives Board for Coordination chaired by the

Secretary-General. Security policies are promulgated

following endorsement by the HLCM. Therefore, these

are not “UNDSS policies”; they are system-wide policies

endorsed at the highest level of the United Nations

system. We usually refer to these policies as “UNSMS

policies”. The graphic below shows how the work of

each group on policy ts together.

Fig. 2: A representation of the UNSMS policy-making process. UNSMS

policies approved by the HLCM are generally drafted by IASMN working

groups.

16

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

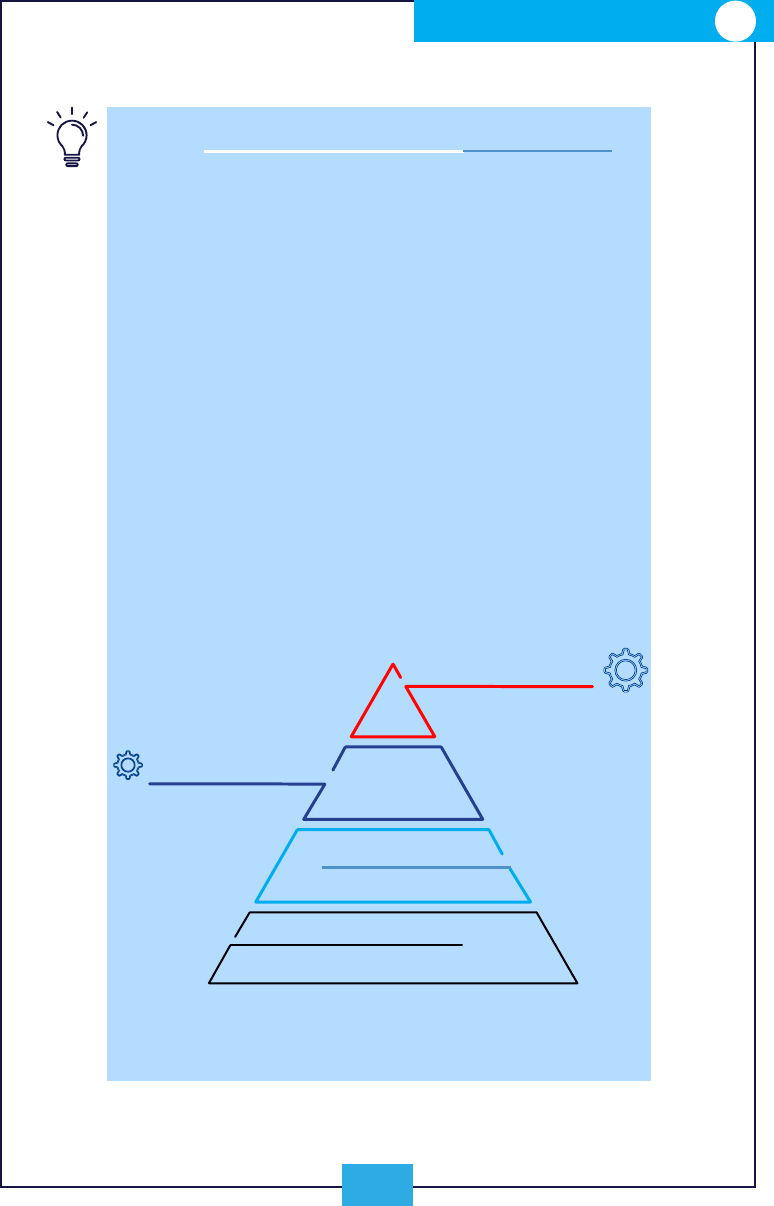

SECURITY POLICY FRAMEWORK

All UNSMS policy materials are subordinate to, and consistent with,

the legislative issuances of the inter-governmental bodies, United

Nations Staff Regulations and Rules and system-wide policies of the

Secretary-General. UNSMS policy material is endorsed at the highest

level of the United Nations system and is applicable system-wide.

Policy: commits UNSMS organizations and personnel to a set of

global principles and objectives. Compliance is mandatory.

Guidelines: offer additional practicalities of how to implement a

policy and may include good practices.

Manual: provides detailed technical instructions on how to carry out

specic tasks related to a security policy or guidelines.

Handbook: gives information on a policy area or assists a particular

audience in performing their role(s).

Aide-Memoire: offers a summary or outline of important policy

guidance. In some instances, this may be a template or another

document that should be updated for a Designated Area.

UNDSS Communiqué: used by USG UNDSS to send communications

across the UNSMS. Policies and Guidelines are always initially

promulgated through a UNDSS Communiqué. Communiqués are also

used to disseminate a variety of UNSMS operational messages such

as evacuation instructions, threat warnings or distribution of new

equipment standards.

17

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTIONS

AND FRAMEWORK

The UNSMS policy on “Relations with Host Countries on Security

Issues” outlines the need for the DO, the SMT and United Nations

security professionals to review the host Government’s capacity to

carry out its responsibilities for protecting the United Nations, and

to identify, reinforce and supplement any shortfalls in this capacity.

The policy also identies key aspects of collaboration with the host

Government on security related issues. It is an essential part of the

responsibility of the DO to ensure that the UNDSS security team

establishes and maintains a dialogue and collaboration with the local

authorities. Another important aspect of the DO’s responsibility is

to pursue with the host Government that the perpetrators of crimes

against United Nations personnel are brought to justice by the host

Government, in accordance with relevant legal instruments.

Q. Do security policies vary between UN agencies?

If so, who is responsible for which security measures

are taken to protect personnel in the eld?

A. UN agencies, funds and programmes are members of the

UNSMS. As such, they participate in and contribute to the

development of all security policies and are bound by them.

There is only one set of approved UN security policies.

Where policies allow for exibility in implementation,

agencies, funds and programmes may have variances, but

the mandatory policy aspects must be adhered to by all.

18

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

1

Legal and Policy Framework

1. United Nations Charter – articles 104 and 105

2. Conventions on Privileges and Immunities of the

United Nations (1946 and 1947)

3. Convention on Safety and Security of United Nations

Personnel and Associated Personnel (1994), and its

Optional Protocol (2005)

4. UNSMS Security Policy Manual (updated regularly

with new and revised policies)

5. Annual Resolutions of the General Assembly on the

“Safety and Security of Humanitarian Personnel and

Protection of United Nations Personnel”

Compliance with Security Policies and Procedures

To ensure that its policies remain robust, the UNSMS

has established a policy feedback loop that includes

the monitoring of compliance status. Compliance

monitoring consists of general and specic techniques

that may include self-assessment, peer reviews,

continuous document reviews and compliance audits.

The DO should report cases of non-compliance

to the applicable UNSMS organization, so that the

organization can take corrective actions, and inform

USG UNDSS to facilitate follow-up at the headquarters

level.

OPERATIONAL

GUIDANCE

2

20

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

C

hapter 1 of this handbook outlined the legal and policy

frameworks for the day-to-day roles of DOs and SMTs. This

chapter explains the broad security architecture in-country

and provides an in-depth overview of the SRM process that guides

security decision-making.

SECURITY ARCHITECTURE IN-COUNTRY

The Framework of Accountability provides guidance on the roles

and responsibilities of all security actors in the UNSMS. DOs are

accountable to the Secretary-General, through the USG UNDSS, for

the safety and security of all individuals covered by the UNSMS in

their Designated Area.

The DO is required to nominate at least three persons that

could serve as DO a.i. Such nominees shall be heads of UNSMS

organizations at the Designated Area, members of the SMT and

accredited to the host Government. All nominated DOs a.i. shall

obtain clearance from their respective parent organizations before

accepting the DO’s nomination. Prior to any absence from the

Designated Area, DOs shall ensure that one of the appointed DOs

a.i. remains in the Area.

In this regard, the DO will be supported by a range of United Nations

security professionals and the SMT, as well as the USG UNDSS.

Security Management Team

The SMT provides advice and support to the DO on all security-

related matters and comprises the heads of all UNSMS entities/

organizations with presence in the Designated Area. These

representatives are accountable to the Secretary-General,

through their Executive Directors, for the safety and security of

all individuals of their organization.

The role of SMT members is to advise the DO on the particular

concerns of their organizations regarding security and

ensure that activities of their organizations are conducted in

compliance with the applicable decisions. They also ensure that

safety and security considerations are a core component of

21

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

their programmes and are adequately funded at the local level,

and that their personnel comply with all related instructions and

requirements.

It is important that the DO provide effective leadership to the

SMT and chair the meeting in-person. Though decisions are

normally made in a consultative manner reecting the views and

recommendations of SMT members, the DO is responsible and

accountable for making the nal decision on security-related

issues. In the event that a rapid decision is required to avoid loss

of life or to resolve an impasse at the SMT level, the USG UNDSS

may convene the Executive Group on Security, comprised of

Executive Heads of a number of UNSMS organizations, to advise

and assist in rapidly resolving a security impasse. An Executive

Group on Security meeting may also be called should the DO

request the USG UNDSS to do so.

It is also important that the DO convene regular meetings of the

SMT, at a frequency determined by the SRM, and at least once

a year. Minutes of each SMT meeting must be prepared, shared

with SMT members for review and, when nalized, forwarded to

UNDSS Headquarters. All members must receive SMT training

prior to participating in the meetings.

The SMT comprises the head of each UNSMS organization

present in the Designated Area. In peace operations, where

the Head of Mission serves as the DO, the SMT may also

include heads of components, or oces, as specied by the

DO. Heads of military and police components of peacekeeping

missions are always members of the SMT.

Who is part of the SMT?

22

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

Training for DOs & the SMT

Area Security Coordinators and Area SMTs

It is mandatory for DOs a.i., all members of SMTs and Area

Security Coordinators to complete training specic to their

security roles. At a minimum, the online SMT training module

must be completed, and a record of certication maintained.

DOs a.i. are also required to complete a mandatory security

orientation course at either New York Headquarters or

virtually, ideally prior to assuming their role in the country of

assignment. This mandatory training also applies to those

who have already been DOs for extended periods of time or

are changing duty stations.

In addition, there may be other training requirements at the

local level.

As a reminder, DOs and SMT members are accountable for

ensuring that all personnel complete the requisite mandatory

training BSAFE, as well as other training requirements

determined for the Designated Areas as per the SRM process.

Contrary to the earlier versions of the BSAFE training (Basic

and Advanced Security in the Field courses), there are no

limits on the course’s validity and, once completed, it does

not have to be retaken. Personnel may be encouraged,

however, to revisit the training to refresh their knowledge.

Area Security Coordinator

In a large Designated Area with locations far from the capital, the

DO, in consultation with the SMT, may appoint in writing an Area

Security Coordinator (ASC) for each area. The ASC is responsible

for coordinating security arrangements applicable to all

personnel, premises and assets in their areas of responsibility

(called “Security Area”).

The ASC is accountable to the DO for his or her security-related

responsibilities. The ASC must establish an Area Security

Management Team (ASMT) comprising of heads or senior

personnel of all UNSMS organizations in the Security Area, as

well as an Area Security Cell.

23

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Security Professionals

Various categories of security professionals are deployed to

assist the DO and the ASC in the discharge of their responsibilities:

• The Principal Security Adviser, Chief Security Adviser or

Security Adviser (P/C/SA) is a UNDSS staff member and

senior security professional appointed to advise the DO and

SMT in their respective security roles. They can have regional

functions and advise DOs and SMTs in several countries.

This senior UNDSS representative reports directly to the

DO and maintains a technical line of communication on

operational matters to UNDSS Headquarters in New York.

Minutes of ASMT meetings should be provided to the DO and

the SMT for further review and endorsement. The ASC and the

Area Security Management Team are essentially subordinate

versions of the DO and SMT.

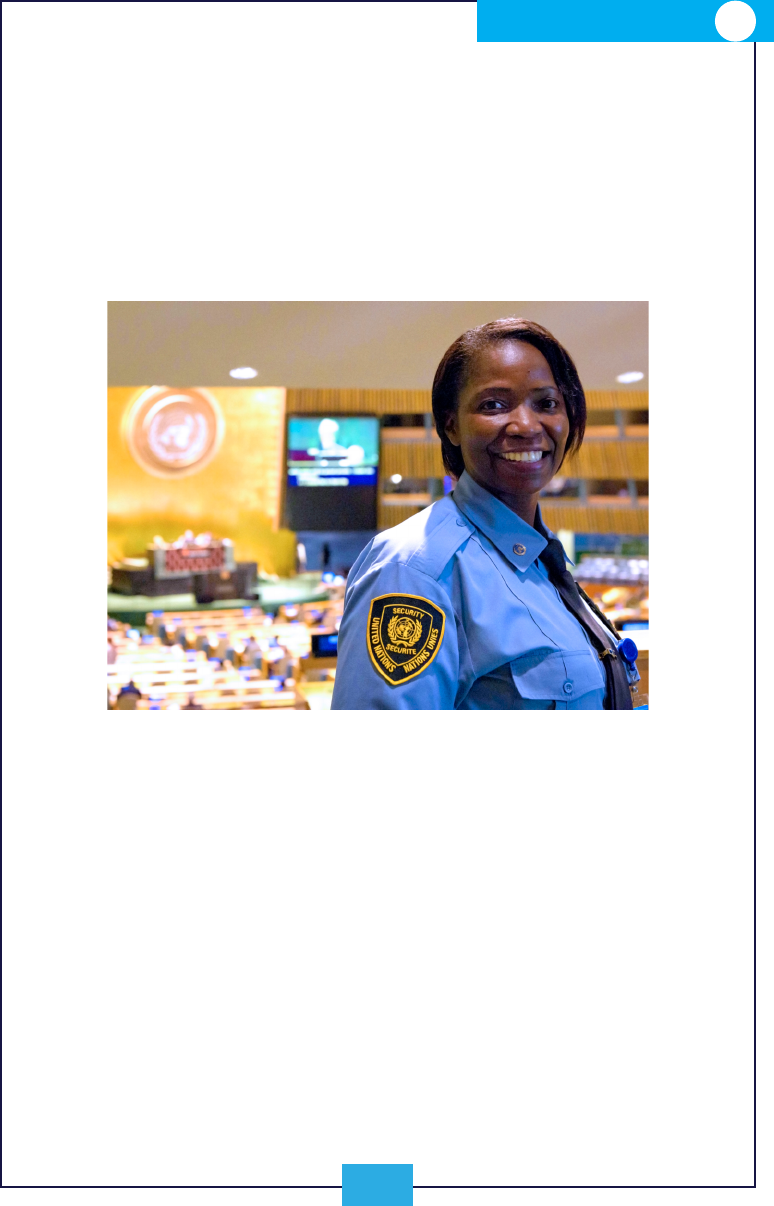

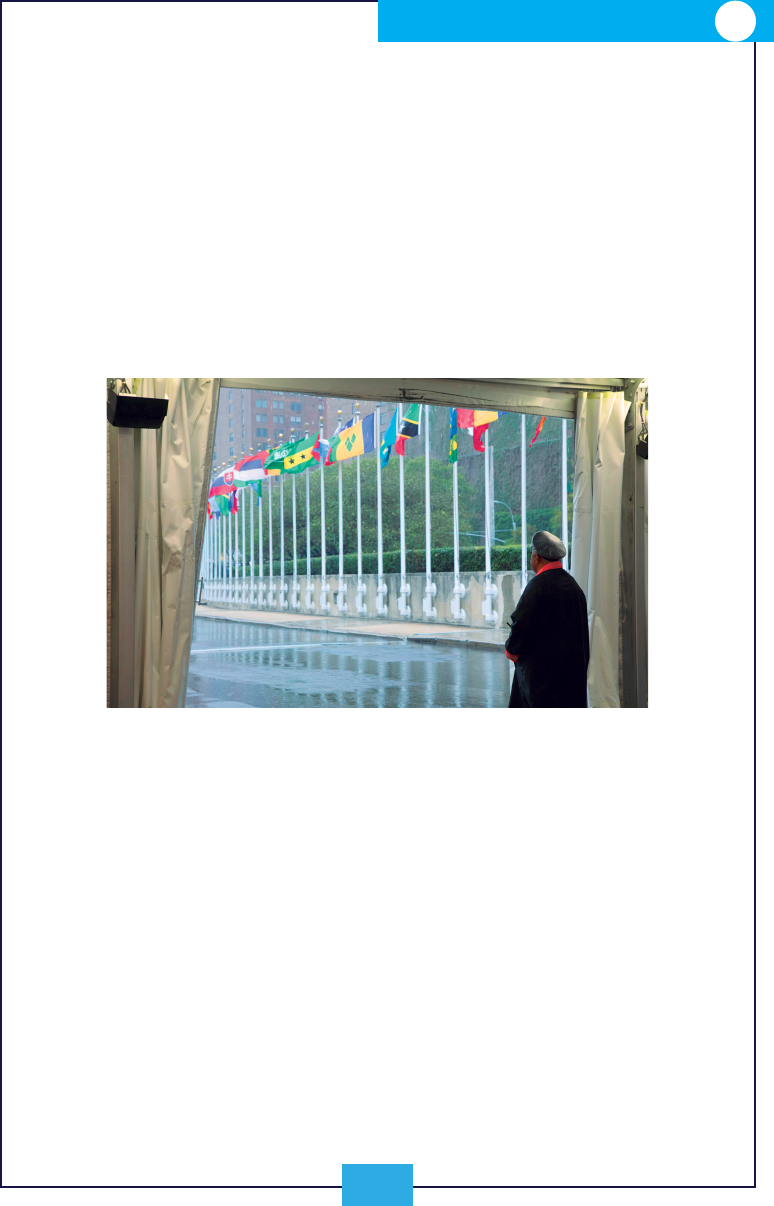

A UNDSS ocer on duty during the Nelson Mandela Peace Summit./UN Photo

24

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

• In integrated peacekeeping or special political missions,

the senior UNDSS representative also manages the security

section of the mission and the operational management

of security across the country. In some non-integrated

peacekeeping missions where the Head of Mission is the DO

for a specic Designated Area, the mission’s Chief Security

Ocer acts as the primary security adviser to the DO in the

absence of a UNDSS-appointed security professional.

• The senior UNDSS representative and Chief Security Ocer

directly supervise an Integrated Security Workforce (i.e.

security personnel from UNDSS and from the mission)

whose size varies depending on various factors including

size of mission, geography and risk. These include Field

Security Coordination Ocers, Security Information

Analysts, Security Operations Ocers, Mission Security

Ocers and Local Security Assistants. In very complex

environments, the security structure may be further

reinforced by a Security Information and Operations Centre

to perform analytic and coordinating functions.

• Single-Agency Security Ocers of UNSMS organizations

may be deployed to specic Designated Areas or with a

regional coverage to advise their organization and take

responsibility for security specic to their organization’s

activities. These Security Ocers are accountable to

their organization, although they do have an obligation

to support the Security Cell under the coordination of

the senior UNDSS representative. In the absence of a

UNDSS representative, Single-Agency Security Ocers

can be appointed by UNDSS as the Security Adviser

a.i., in consultation with their respective organization.

In Oces away from Headquarters, Regional Commissions

and International Tribunals, security functions are managed

by the Chief of Security and Safety Services. The Chief

is responsible for the management of Security and

Safety Services/Sections, including uniformed UNDSS

Security Ocers. In some locations, the USG UNDSS can

appoint the Chief of Security and Safety Services as the

Principal or Chief Security Adviser for a Designated Area.

25

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Security Cell

In order to ensure the ecient and effective use of resources and

ascertain that all Security Ocers at the Designated Area work

to further the SRM process, the senior UNDSS representative

establishes and chairs a Security Cell. The Security Cell includes

Single-Agency Security Ocers who advise on particular

concerns of their organization regarding security, as well as

local Security Focal Points of UNSMS entities.

In practice, and in locations where the senior UNDSS

representative has established a Security Cell, security-related

matters addressed at the SMT should rst be addressed at the

Security Cell level. With the agreement of the SMT member,

Security Cell members attend the SMT as observers.

Wardens

Wardens are not security professionals, yet they hold

specic security responsibilities. They are selected among

internationally and locally recruited personnel and appointed

in writing by the DO, in consultation with the SMT, to assist in

the implementation of the Area Security Plan. (Please see page

46 for more on the security plans). Wardens are accountable to

the DO for their security-related functions, irrespective of their

employing organization, and are responsible for communicating

with personnel, their eligible family members and visitors

in times of crisis. The Warden System can be zone-based

(responsible for communicating on security with all personnel in

a specic geographic area) or organization-based (responsible

for communicating on security within their organization).

United Nations Personnel

All United Nations personnel in the Designated Area have

a responsibility to abide by security policies, guidelines,

directives, plans and procedures of the UNSMS, in accordance

with the Framework of Accountability. United Nations personnel

are those covered under the Applicability Policy. The leadership

26

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

of the DO, as well as of heads of UNSMS organizations, is

instrumental to cultivating a “security culture” in-country. This

means leadership teams must ensure that personnel familiarize

themselves with security management information relevant

to their location and duty station, attend and complete the

necessary security training and required briengs, and report all

security incidents in a timely manner. Finally, all United Nations

personnel must conduct themselves in a manner that will not

endanger their own safety and security or that of others.

The DO is responsible for the provision of Area SRM processes,

as well as ad-hoc SRM processes. Although the senior UNDSS

representative and the UNDSS team will guide these processes,

DOs are expected to be familiar with them and lead the SMT

to endorse the nal product. In each country, a number of

SRM processes may be completed depending on the size and

complexity of the country and United Nations presence.

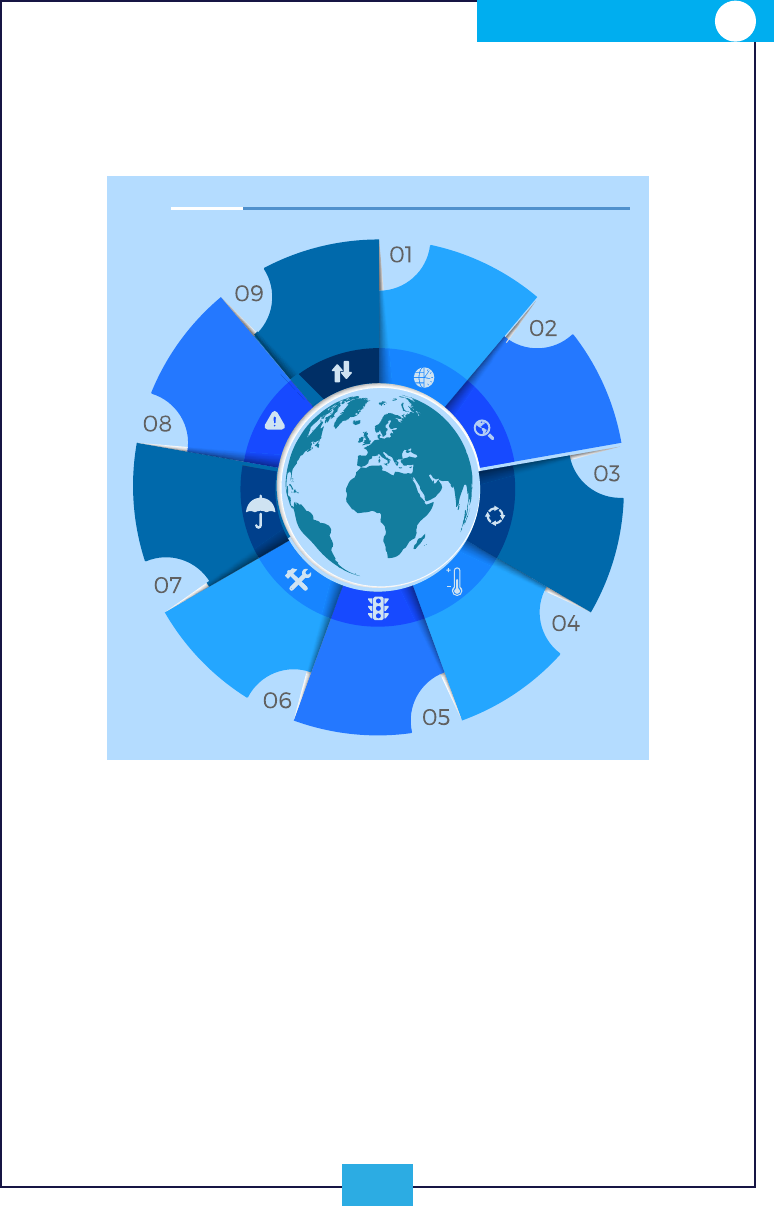

There are nine steps to the SRM process, outlined in the

following pages. The mandatory SMT training also provides

further information on this process, and the DO is encouraged

to consult with the senior UNDSS representative for additional

expertise and advice.

Our Security Obligations

1. Familiarize ourselves with security information provided

at the location

2. Obtain security clearance prior to traveling

3. Attend security briengs

4. Know our wardens and security professionals

5. Be appropriately equipped for service at the duty station

6. Comply with all UNSMS regulations and procedures, both

on/off duty

7. Comport ourselves in a manner which will not endanger

our safety and security or that of others

8. Report all security incidents in a timely manner

9. Complete BSAFE

10. Complete security training relevant to level and role

27

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

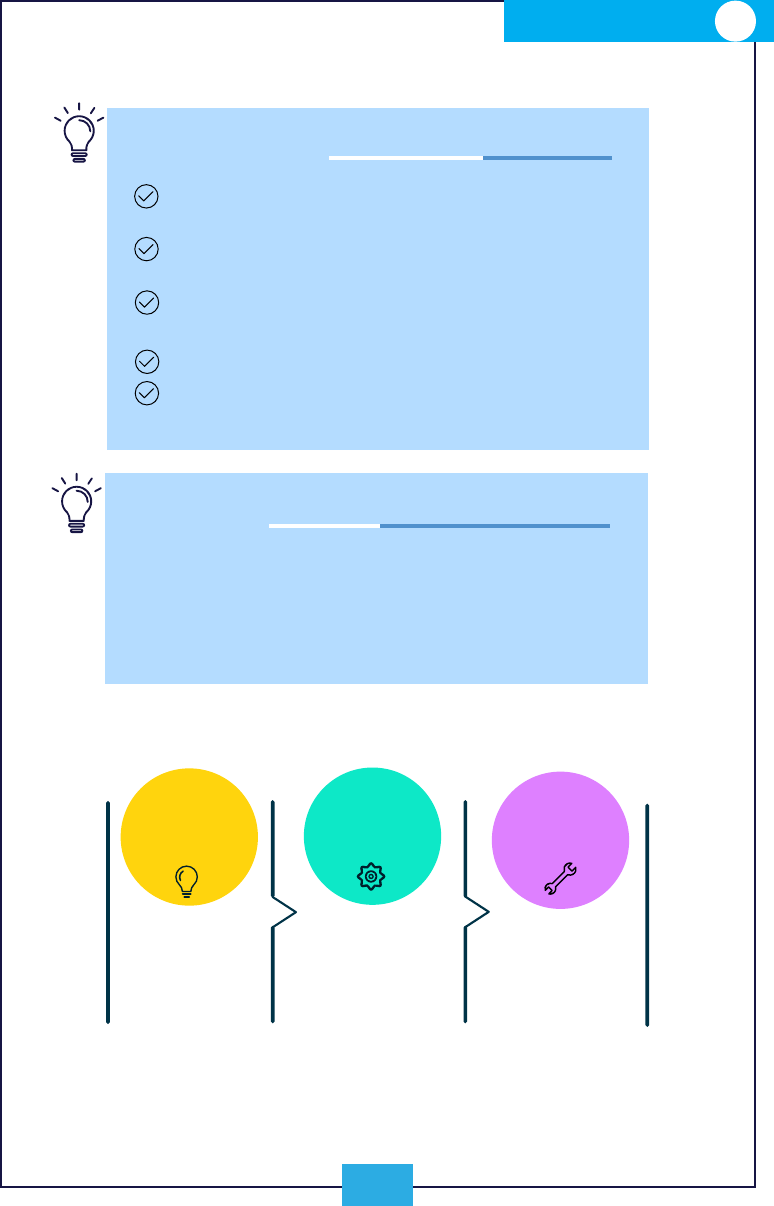

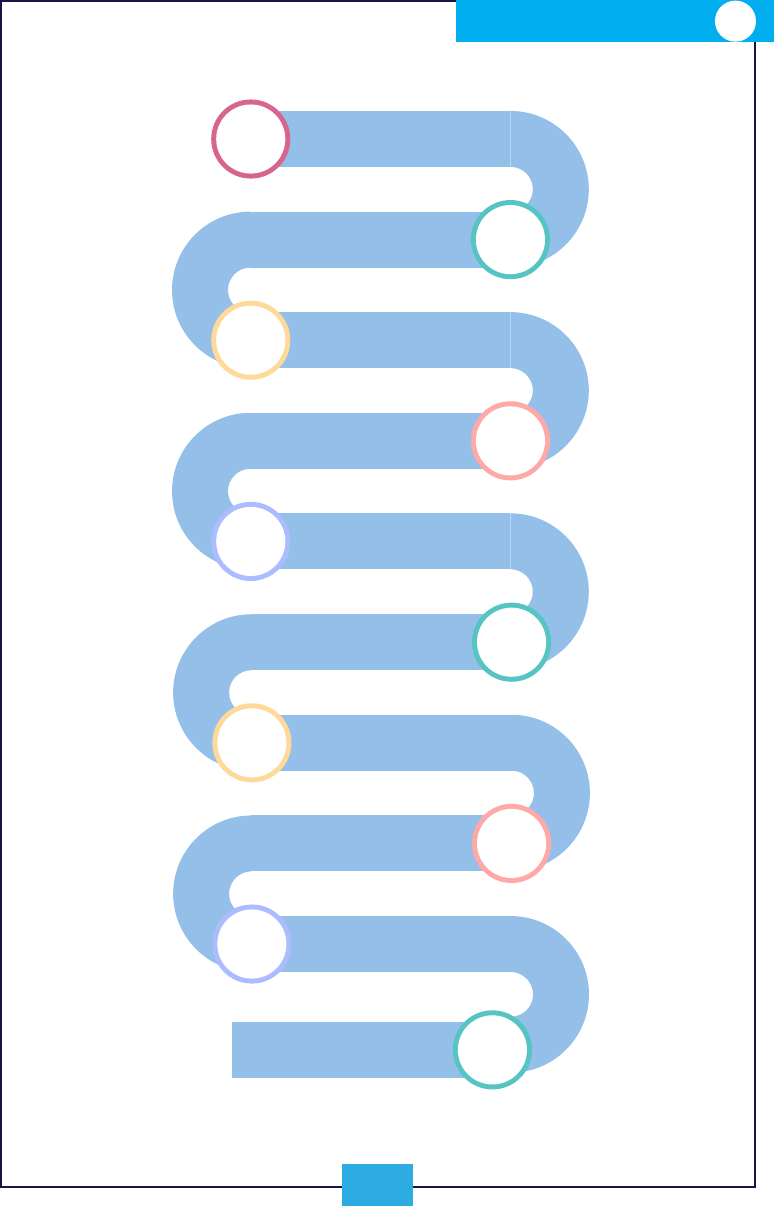

SRM Process

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4

Step 5

Step 6

Step 7

Step 8

Step 9

ACCEPTABLE

RISK

REVIEW

SITUATIONAL

ANALYSIS

PROGRAMME

ASSESSMENT

THREAT

ASSESSMENT

SECURITY RISK

ASSESSMENT

SRM

MEASURES

SRM

IMPLEMENTATION

GEOGRAPHICAL

SCOPE AND

TIMEFRAME

SECURITY RISK MANAGEMENT

Security Risk Management is the UNSMS tool to identify, analyze

and manage safety and security risks to United Nations personnel,

assets and operations.

The SRM process is guided by a UNSMS policy, and supported by a

manual which provides step-by step guidance to security personnel

on the process. This approach was rst established in 2004 and

last updated in 2019 with additional guidelines, training tools and

templates.

Fig 3: The SRM process is a structured, problem-solving mechanism that consists of

nine steps.

28

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

Setting the Geographical Scope and Timeframe

The initial step in the SRM process is establishing the geography

and timeframe of the SRM. This comprises a Designated Area, a

Security Area (usually the area of responsibility of an ASC) and

any specic SRM Area. An SRM area is determined at the country

level by the SMT, and is usually an area of homogenous threats

for which a specic assessment is carried out (such as a conict

area). The SRM Area is the geographical scope at which the DO

applies the SRM process. The timeframe for each SRM process

may be determined by an event (such as an election period), or

within a reasonable review period (usually 3, 6 or 12 months).

Situational Analysis

A common understanding of the security situation is vital for

responsible decision makers. The situational analysis considers

the political, economic, social and environmental status in each

area, and examines how developments in these areas may

impact the safety and security of United Nations activities. It

also considers the United Nations mandate and/or strategic

priorities and how these could potentially affect the security

situation or United Nations personnel, assets and operations, as

well as threat groups/actors.

Programme Assessment

This assessment is the process by which the goals and

specic implementation activities of all UNSMS organizations

in-country are formally identied and assessed for any threat-

related implications. Sucient details must be provided about

the programmes to be delivered - both generally (such as within

over-arching mission goals) and specic to each programme.

Risk-Based vs Threat-Based?

It is very important to understand that the UNSMS is risk-

based, not threat-based. While threats are assessed as part

of the process, decisions are taken based on the assessment

of risk.

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

29

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Threat Assessment

The Threat Assessment is the assessment of those actors

and actions in the SRM area that may potentially cause harm

to the United Nations system. These are assessed in the

following categories: Armed Conict, Terrorism, Crime and

Civil Unrest. The intent and capabilities of the relevant threat

actors are identied and assessed, along with the Inhibiting

Context, which acts as a “restrainer” of the threats. In locations

where UNDSS Security Information Analysts are present, their

assessments will form a vital part of this process. The Threat

Assessment ends with event descriptions, which are essentially

forecasts for how specic threats might occur in the future.

Security Risk Assessment

The Security Risk Assessment is the process by which the

different threats of the United Nations presence and activities in-

country are assessed against the existing vulnerabilities in order

to determine the likelihood of a harmful threat event occurring,

and the impact this may have on United Nations personnel,

assets and operations. A risk matrix is used to determine the

overall risk.

Security Risk Management Measures

This step is the process by which measures and procedures to

lower the risks - called SRM measures - are decided. This then

results in the residual risk. All measures identied must be

Step 4

Step 5

Step 6

Gender considerations in the SRM

The SRM must be gender sensitive and gender-responsive.

All gender-based threats, risks and vulnerabilities should

be considered in the SRM process, including during risk

analysis, identifying SRM measures for gender-related

security incidents, managing stress and reporting gender-

related security incidents. SRM measures, including for

residences, should be reviewed on a regular basis with a

gender perspective.

30

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

directly linked to the preceding assessment, assisting to reduce

either the likelihood (prevention) or the impact (mitigation)

of an event, or both. SRM measures may include information,

training, briengs, specialist resources, equipment, physical

improvements to premises or facilities, or procedural changes.

When selecting SRM measures, it is important to consider the

time, cost and potential adverse impact of any decisions taken.

Each measure will have strengths and weaknesses. The nal

decision of the DO should take these into account.

SRM Implementation

Once a decision is made, the SRM measures must be

implemented, including through the allocation of resources

where required. If the SRM measures are not implemented

effectively, the SRM process fails, as risk is not being managed

and reduced. The leadership of the DO and the implementation

by the SMT is vital to ensuring the effective management of

security risks.

Acceptable Risk Decisions

ACCEPTABLE RISK DECISION = BALANCING RISK

AGAINST CRITICALITY

a. Do not accept unnecessary risk

b. Accept risk when benets outweigh costs

c. Make risk management decisions at the right level

Step 7

Which measures are mandatory?

SRM measures that have been approved by the DO, on the

recommendation of the SMT, are mandatory in the SRM Area.

These approved SRM measures are sometimes referred to as

MOSS.

31

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Acceptable Risk

The Acceptable Risk Model includes the Programme Criticality

Framework, as briey introduced on pages 13 and 14. This

model has three important principles to aid in the balancing of

risks, highlighted in the box on page 30.

Under the Acceptable Risk Model, whether the risk of a given

programme activity is acceptable will depend on the criticality

of a programme (as determined by the United Nations Country

Team (UNCT) through a Programme Criticality exercise),

considered against the existing risk (as determined by the SRM

process outlined above.) As Resident Coordinator/Humanitarian

Coordinator or the Special Representative of the Secretary

General, the DO is responsible for ensuring the Programme

Criticality process has been carried out. The DO is also

responsible for ensuring that, when the risk is high or very high,

Fig 4: The approval of SRM measures follows a multi-step process. UNDSS

Headquarters Desk Ocers maintain oversight throughout to provide support where

required or requested.

Considering advice of SMT members,

DO decides at SMT meeting whether to approve SRM.

SRM Measures will become MOSS for Designated Area.

DO decides on SRM

SMT members have minimum four weeks to consider measures.

At this time they seek endorsement, support and advice from HQs.

SMT considers SRM

Senior UNDSS security officer in-country presents SRM Measures to

DO and SMT as part of SRM process for each Designated Area.

UNDSS presents SRM

Step 8

32

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

the correct approvals are sought and received for programme

activity depending on the levels of risk.

Follow up and Review

The purpose of monitoring and evaluating the SRM process is

to assess and improve the effectiveness of the SRM measures,

or to remove or downgrade the measures as necessary. This

process can take place through routine monitoring by the SMT,

or through UNDSS internal processes such as spot checks or

review by the UNDSS DRO Desk Ocers.

Step 9

Acceptance

The SRM should take into account acceptance, which can

be considered in the situational analysis, the programme

and threat assessments and the security risk assessment

steps of the process. The SMT should encourage the

implementation of measures such as communication

campaigns, stakeholder/beneciary meetings, negotiations,

or other engagement with threat actors, where appropriate,

in order to help secure acceptance. Acceptance can be

dened as “good relations and consent as part of a security

management strategy with local communities, parties to the

conict, and other relevant stakeholders and obtaining their

acceptance and consent for the humanitarian organization’s

presence and its work.” Its goal is to facilitate programme

delivery.

33

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

SPECIFIC SRM MEASURES

The results of the SRM may lead to any number of risk management

measures that require implementation. There are four main

strategies for managing risk (below).

Of these, measures to avoid risk, including alternate work modalities

and personnel and/or family restrictions, may be considered on

a temporary basis. These measures have considerable physical

and administrative impact to United Nations personnel and/or

programmes and, as such, the DO and SMT should be familiar with

the terms and the administrative implications, as highlighted below.

Alternate Work Modalities: These refer to measures which limit or

totally remove the number of personnel or family members present

during working hours at a specic location(s) with the view to limit or

remove their exposure to unacceptable risk. Such measures could

include: temporarily limiting the number of personnel at a United

Nations premises, temporarily closing oces or establishing work-

from-home arrangements.

Personnel and/or Family Restrictions: Temporary restrictions are

placed on the presence of any or all personnel and/or eligible family

members of United Nations internationally recruited personnel at a

given location or area. They can include relocation or evacuation,

as follows.

Main Strategies for Managing Risk

• Accept the risk (no further action)

• Control the risk (using prevention and/or mitigation

measures)

• Avoid the risk (temporarily distance the target from the

threat)

• Transfer the risk (insurance, sub-contracts or other

measures)

34

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

• Relocation: Relocation is the ocial movement of any

personnel or eligible dependants from their normal place

of assignment or place of work to another location within

their country of assignment for the purpose of avoiding

unacceptable risk. Relocation can be applied to all

personnel and eligible family members. Entitlements are

applicable.

• Evacuation: Evacuation is the ocial movement of

international personnel and their eligible dependants from

their place of assignment to a location outside of their

country of assignment (safe haven country, home country

or third country). It may apply to locally recruited personnel

in exceptional circumstances and with the approval

of the Secretary-General. Entitlements are applicable.

The decision to relocate and/or evacuate is submitted

through the USG UNDSS to the Secretary-General on the

recommendation of the DO. In the event of an evacuation,

the USG UNDSS will distribute an All Agency Communiqué

to advise of the details, and will notify UNSMS entities of

any change or cessation of the relocation/evacuation.

In regards to the entitlements due to evacuation, individual parent

organizations are responsible for all nancial arrangements,

including the payment of salary advances, allowances or other

essential payments to their personnel as necessary. Further,

individual organizations may have additional provisions and

guidance for their personnel in the event of relocation or evacuation.

For example, representatives of organizations participating in the

UNSMS may institute Alternate Work Modalities solely for their

personnel in response to agency-specic risks and inform the SMT

and the senior UNDSS representative.

Personnel Evacuated from Kitchanga, North Kivu./UN Photo

35

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

2

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Evacuation of United Nations Personnel from Yemen

Case Study: March 2015

The evacuation of United Nations personnel from Yemen

was implemented after the intense aerial bombardment

of various targets in the country on 25 March 2015.

International UNSMS personnel were evacuated from

Aden, Al Hudaydah and Sana’a to neighboring countries

(Djibouti, Egypt and Ethiopia) in the following days. The

review of the event identied lessons and best practices

in relation to the crisis response, security arrangements

and evacuation procedures.

1. Comprehensive and detailed security planning is

essential in strengthening the level of preparedness. The

evacuation plan should contain a detailed description

of the arrangements, alternative triggers and means of

evacuation to allow evacuations to be implemented in an

organized and coordinated manner.

2. Effective implementation of SRM measures to lower

the residual risk is essential for continued UN presence

and continued programme operation. The purpose of

authorizing a small humanitarian coordination group of

international personnel to remain on the ground was to

coordinate critical humanitarian activities, in line with

PC1 activities. However, operations cannot be conducted

if there is no investment in, and implementation of, risk

management measures.

3. Clearly dened roles and responsibilities of personnel

involved during the evacuation, including the support

by security professionals of UNSMS organizations, are

crucial for the ecient management of a large number

of personnel at concentration points. This includes the

timely appointment of the SA a.i. and the Deputy SA a.i.

and the delegation of responsibility to locally recruited

personnel to enable structured liaison and clear chain of

accountability for security arrangements.

36

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

2

OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE

The eTA app

In 2019, UNDSS released an application called eTA,

which provides resources such as security clearance

information and travel advisories for personnel of United

Nations departments, agencies, funds and programmes.

The application is available to all UN personnel. Its use

is approved by the DO at the local level through the SRM

process.

TRIP: Security Clearance

It is mandatory for the DO to manage security clearance

procedures for internal and external travel to the Designated

Area. To assist with this responsibility, UNDSS manages a web-

based system called the Travel Request Information Process

(TRIP). Security clearance procedures are required so that the DO

can monitor the location and number of United Nations system

personnel and eligible family members, ensure they are included

in the Country Security Plan and to communicate important

security information in the event of a crisis or emergency. DOs

may further delegate their authority to grant security clearances,

generally to the senior-most security professional directly

supporting them.

While this is not mandatory, personnel are encouraged to record

personal travels in TRIP so that they may receive assistance in

a crisis.

CRISIS

MANAGEMENT

3

38

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

T

he preceding chapters outlined the regular security duties

and responsibilities of the DO and the SMT. This chapter lays

out the practical steps to take in case of a safety and security

crisis, as well as the necessary advance preparations.

The effective management of security crises is a crucial component

of the leadership of the DO supported by the SMT. This responsibility

includes ensuring appropriate preparation and response in the

event of a security crisis impacting United Nations personnel. DOs

shall make every effort to ensure that all preparedness measures

for security crises are undertaken in the Designated Area in line with

the level of threat and security risk.

UN-WIDE CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Crisis management across the organization is guided by the United

Nations Crisis Management Policy (2016, revised 2018). This policy

species that the senior-most UN ocial in country is responsible

and accountable for coordinating the management of the UN

response to the crisis in country. Depending on the nature of the

crisis, different UN entities have coordinating responsibilities.

UNDSS coordinates the crisis response for major safety and

security incidents and/or hostage incidents. Other types of crises

are coordinated by different entities: humanitarian crisis situations

are coordinated by the Emergency Relief Coordinator through the

United Nations Oce for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs;

crisis in peace operations are managed by the Department of Peace

Operations (DPO) or the Department of Political and Peacebuilding

Affairs (DPPA); the Oce of the United Nations High Commissioner

for Human Rights leads crisis in the event of grave violations of

human rights; and serious health emergencies rising to the level of

Public Health Emergency of International Concern are coordinated

by the World Health Organization.

The United Nations Crisis Management Policy is overarching and

strategic. It explains how UN actors should coordinate to respond

collectively to complex situations that require a multidisciplinary

approach. The Guidelines on Management of Safety and Security

Crisis Situations are in line with the system-wide policy and provide

operational guidance to the UNSMS.

39

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

What’s the dierence between the UNSMS guidelines and

the system-wide policy?

The policy is strategic, while the guidelines are operational.

The policy also applies to all crisis situations, while the

guidelines are specic to the management of safety and

security crises.

Other lead entities have promulgated Standard Operating Procedures

(SOPs) to guide crisis arrangements at HQ (SOP on Headquarters

Crisis Response in Support of Peacekeeping Operations and SOP on

DPA [now DPPA] Headquarters Arrangements in support of Crisis

Response at the Field Level).

Effective leadership in crisis management:

Take charge quickly and rmly, using your crisis team to best

effect to provide advice and management on aspects where

you lack knowledge;

Make sure you have good situational awareness: what is

happening, why it is happening and what may happen next;

Be clear on your objectives and priorities; review them

regularly to adapt to a changing situation;

Accelerate decision-making to achieve timely, effective

decisions; ensure concurrent activity to achieve rapid action;

Give clear direction and guidance; assign clear responsibilities

for tasks with deadlines;

Focus at strategic and operational level, not detailed

discussions at subordinate level;

Instill a sense of urgency but also inspire condence and

remain calm.

40

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT OF SAFETY AND

SECURITY CRISES

Depending on where the crisis situation is unfolding, either the

DO or ASC will function as the Crisis Manager (except for hostage

incidents). The Crisis Manager has the responsibility and requisite

authority to make critical decisions on the management and

response to safety and security crisis situations. The DO must

convene a Crisis Management Team within 24 hours following the

event of a safety or security crisis, until the emergency is resolved.

What constitutes a “crisis”?

A crisis is dened as an incident or situation, whether natural

or human-made, that due to its magnitude, complexity

or gravity of potential consequence, requires a UN-wide

coordinated multi-disciplinary response. Examples include

natural disasters, inter/intrastate conicts, acts of terrorism,

pandemics or reputational issues, such as multiple cases of

sexual exploitation and abuse.

What dierentiates a “safety* and security crisis” from

other types of crises?

Safety and security crisis is dened as an incident or

situation, whether natural or human-made, that due to its

magnitude, complexity or gravity of potential consequences

presents an exceptional risk to the safety and security of

UNSMS personnel, premises and assets. Often, safety and

security crisis situations are part of broader political, military

or humanitarian crises. In such complex contingencies, all

United Nations crisis management pillars, including safety

and security, must work together.

*The UNSMS covers three areas of safety: re, road and air travel safety.

41

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

The Crisis Management Team will implement and coordinate

decisions made by the Crisis Manager. To coordinate specic

operational aspects of the crisis response, the DO may also

designate a Crisis Coordinator. In country team settings, where the

Resident Coordinator or Executive Director is the designated crisis

manager, the Principal/Chief or Security Adviser is designated as

the Crisis Coordinator.

Finally, to support the Crisis Management Team and help coordinate,

a Crisis Coordination Centre may also be established and equipped

with adequate communications systems. As noted earlier in the

chapter, UNDSS coordinates the crisis response for major safety

and security incidents.

In the event a rapid decision is required to avoid loss of life or to

resolve an impasse at the SMT level, the USG UNDSS may convene

the Executive Group on Security to assist in decision-making.

While the above-mentioned arrangements are applicable to all

types of United Nations eld presence, specic crisis management

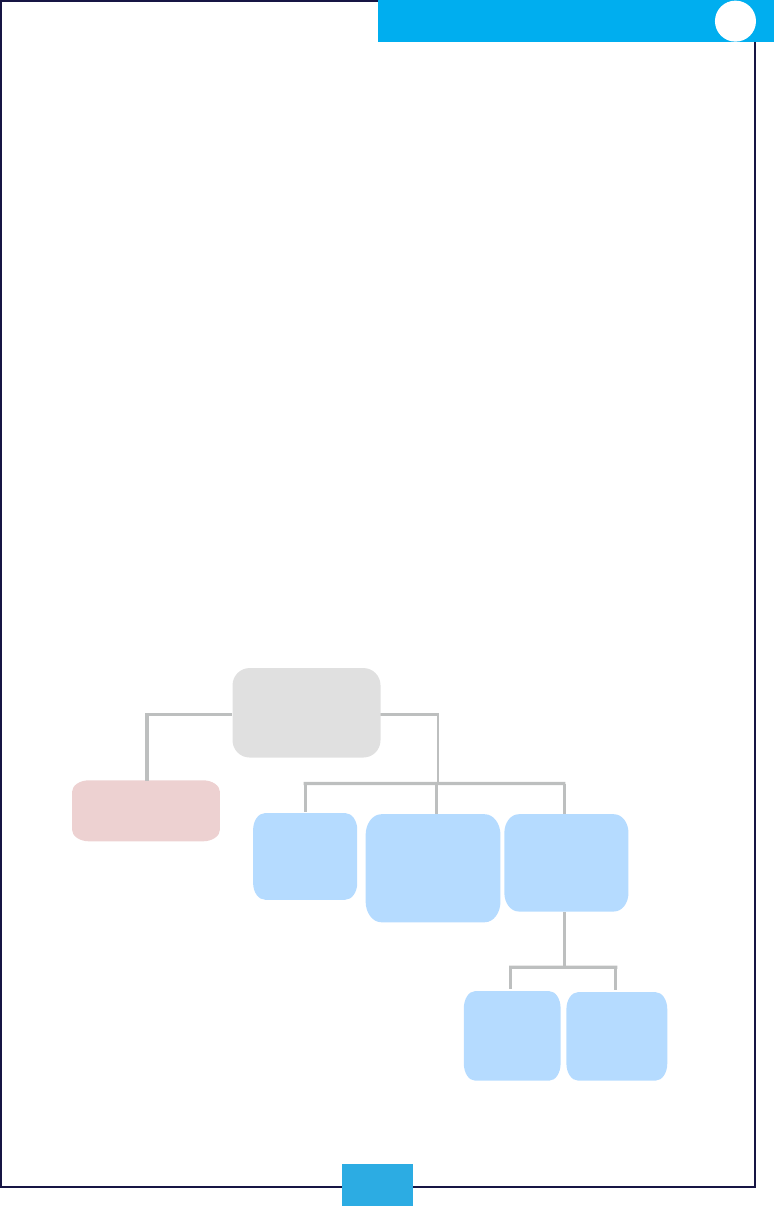

eld architecture may vary depending on the setting. The diagram

on page 43 shows arrangements in a UN Country Team (vs. a UN

peace mission) scenario.

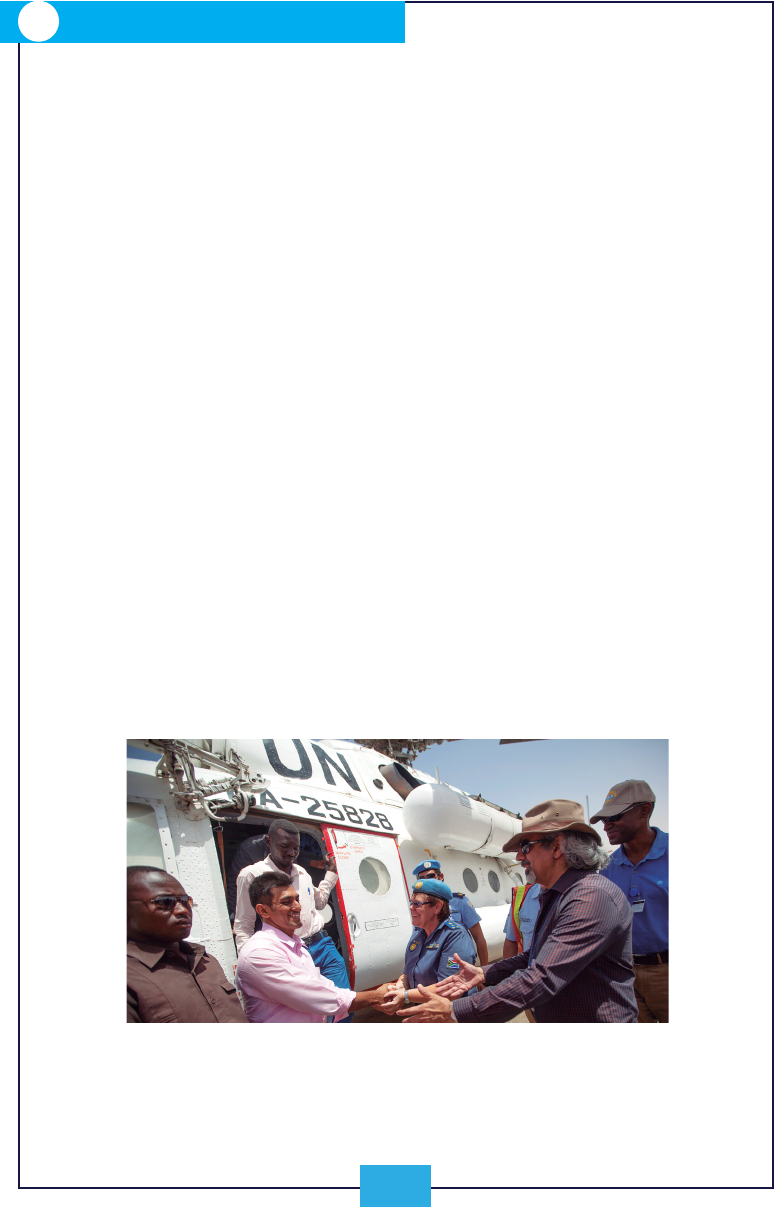

One of two civilian staff members with the African Union-United Nations Hybrid

Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) kidnapped in West Darfur arrives at El Fasher Airport.

/UN Photo

42

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

For Peace Operations

In countries/areas where peacekeeping operations or integrated

special political missions are deployed, the mission Chief of

Staff is generally designated as Crisis Coordinator.

In countries/areas where non-integrated special political

missions are present, the mission Chief of Staff is normally

the designated Crisis Coordinator, if the Head of Mission is the

designated Crisis Manager.

The Crisis Coordinator convenes and chairs an Operations

Coordination Body (OCB), also referred to as the Crisis

Management Working Group (CMWG). The OCB/CMWG

is a working-level, cross-component body responsible for

supporting the Crisis Coordinator in all relevant tasks, such as

supporting day-to-day crisis response activities, making policy

recommendations and ensuring common messaging. The Crisis

Coordinator acts as the link with the Crisis Manager and CMT to

ensure that crisis management objectives are established and

achieved. Existing coordination bodies can be designated as

the OCB/CMWG during a crisis to avoid a proliferation of intra-

mission coordination mechanisms.

The Crisis Manager and the Crisis Coordinator are supported

by a secretariat for crisis management arrangements. In

peacekeeping operations, the secretariat role is undertaken

by the mission’s Joint Operations Centre (JOC), where one

exists, or an equivalent mission component designated by the

Crisis Manager. In integrated special political missions, the

secretariat role may be undertaken by the mission’s Integrated

Information Hub, where one exists, or an equivalent mission

component designated by the Crisis Manager such as the oce

of the Chief of Staff or the Security Information and Operations

Centre (SIOC).

In the non-integrated special political mission setting, a

designated structure, for example the Integrated Information

Hub (IIH) or the SIOC, serves as a 24/7 integrated information

and reporting focal point and as the secretariat for the duration

of the crisis. The JOC/IIH/SIOC, or a designated structure with

similar functions and adequate capability, provides secretariat

support for CMT and/or OCB/CMWG meetings, ensures 24/7

monitoring of and regular reporting on the crisis, acts as the

integrated information centre for all crisis-related information,

and keeps UNHQ updated via the UN Operations and Crisis

Centre and, as required, the respective regional desk of the

Regional Division in the DPPA-DPO Regional Structure.

43

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

DO Crisis Management Response Actions

Activate Crisis Management response and inform USG

UNDSS;

Assume role of Crisis Manager or, where appropriate,

assign ASC to do so;

Establish Crisis Management Team and designate

Crisis Coordinator;

Implement Security Plans;

Set up crisis management reporting and information

platform (Crisis Coordination Centre or equivalent).

Information and Engagement

DOs and UNSMS organizations must include all personnel

- nationally and internationally recruited - in security

planning, as well as inform all of them of what assistance

can be provided by the UNSMS in times of crisis.

Fig. 5: Crisis management architecture in a Country Team Setting

ADVISES

SMT

P/C/SA

DO

CRISIS MANAGER

(DO or ASG)

CRISIS

COORDINATOR

NORMALLY P/C/CSA

DECISIONS

OPERATIONAL

MANAGEMENT

IMPLEMENTATION

TASKS

Crisis Management Team

(UNSMS orgs, experts)

RUNS

Crisis Coordinator Center

CRISIS MANAGEMENT ARCHITECTURE

Country Team setting

44

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Activating Crisis Management Operations

Security crisis management operations are activated whenever

the security situation is (or is likely to be) such that the security

management requirements exceed the ability of the normal

security structures, capacity, processes or procedures to

manage the response effectively. They should be activated

immediately in the aftermath of critical safety and security

incidents affecting UNSMS personnel, including those resulting

from natural disasters, aviation catastrophes, sudden spark of

military hostilities, mass casualty or hostage incidents. They

should be activated partially in situations with developing

political, military, humanitarian crisis or civil unrests, when

severe safety and security consequences to UNSMS personnel

are expected or cannot be ruled out, or where the UNSMS

operates in an environment of critical security incidents or

threats of such incidents.

Information Management

It is important that, during the crisis, relevant information is

collected, collated and disseminated to decision-makers both in

the eld and at headquarters through dedicated channels.

Operational aims of crisis management and response:

Save lives and protect UNSMS personnel

Protect UNSMS premises and assets

Minimize the impact of safety and security crisis on UN

programmes and activities

Ensure preparedness and recovery from impact of safety

and security crisis

Ensure return to UN programme delivery

45

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

CRISIS PREPAREDNESS

Managing safety and security crisis situations in the eld effectively

depends on the level of crisis preparedness achieved through

implementing UNSMS policies and guidelines. Crisis preparation

should also include Saving Lives Together partners. This will enhance

multi-level cooperation, security awareness and build response

capacity of partners through enhanced information sharing and

shared training initiatives. See page 61 for more information.

Crisis Management in Integrated Mission Settings

Case Study: South Sudan

The crisis that took place in Juba, South Sudan, from 8 to

11 July 2016, presented several key lessons which can be

implemented to greatly increase effectiveness in emergency

preparedness planning, respective training and coordination

and implementation of plans in integrated mission settings.

Planning should include a dedicated focal point from national

security; clarication of the command and control structure and

role distribution; and, in addition, be subjected to continuous

review to ensure improvement of the planning processes.

Planning and preparing for large numbers of internally displaced

people entering UN facilities is a critical element of crisis

management planning.

Mission wide crisis management preparedness can be achieved

through training exercises and rehearsals using scenarios and

integrating all necessary UN actors. Greater security training

outreach to partners as advocated in the Saving Lives Together

framework will improve response eciency during management

of crises. Besides making specic provisions for the potential

unique security risks to female personnel in a crisis, any needs

assessment of training activities must also be cognizant of

security risks related to gender. Relevant and targeted training

to those identied at greater risk remains both an essential

mitigation and prevention strategy. Safe and Secure Approaches

in Field Environments (SSAFE) training is one area of training

that develops preparedness for all personnel. Personnel

expressly indicated the value of having received SSAFE training

in advance of the 2016 crisis.

46

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

There are three central areas of preparedness:

A timely, updated SRM document identifying likely threat

scenarios, determining security risks and developing and

implementing SRM measures. (See chapter 2 for more on

the SRM).

The security plan, which outlines planned response actions

to address anticipated threat scenarios. (See section below

for more information.)

Crisis management training and exercises, which should be

conducted periodically (at least annually).

Security Planning

The security plans should include security arrangements such as:

updated and veried lists of internationally and locally recruited

personnel and their eligible family members; an emergency

communication system to provide reliable communications

between the DO, the senior UNDSS ocial, the SMT, Wardens

and relevant United Nations oces outside the country, mass

casualty and medical evacuation plans; and the identication

of concentration points and related means of relocation or

evacuation as required.

1

2

3

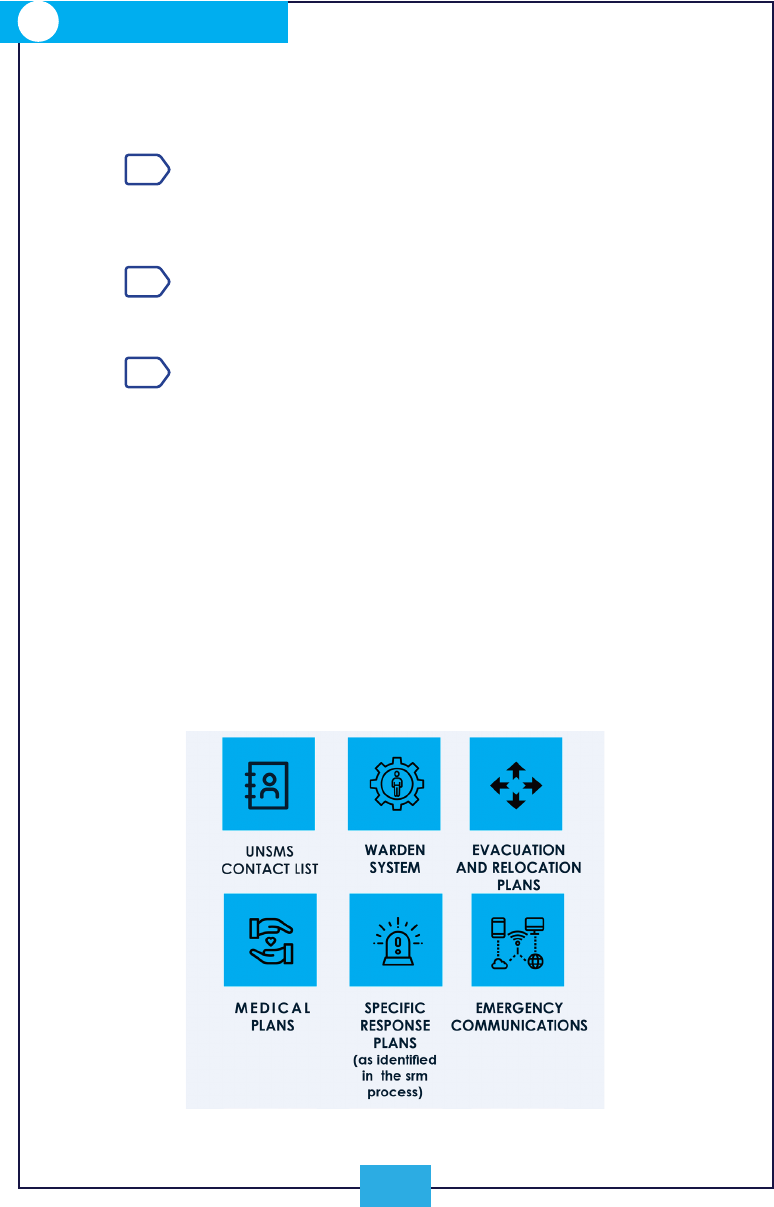

Fig. 6: The security plan consists of six key components.

47

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

Security plans should be regularly maintained and tested,

at minimum on an annual basis. This could be done through

table-top crisis management exercises, evacuation drills and

the activation of warden systems and communications trees.

Exercise scenarios should be built around events and security

threats identied in the SRM process. Preparedness for a range

of contingencies is necessary to ensure an effective response to

crises. ASCs should also test their Area Security Plans at least

as often and, in conjunction, with the country security plan.

While the senior security professional prepares, maintains and

tests Security Plans in collaboration with Security Cells, the DO

has a central role in security planning.

As noted earlier, DOs and UNSMS organizations must include

locally recruited personnel in security planning, and inform them

on what assistance the UNSMS could provide in times of crisis.

The DO:

approves the security plans;

ensures that personnel lists are updated;

liaises with organizations outside the UNSMS;

engages with the Host Government;

approves assistance to other people (outside the UNSMS).

Assistance to other persons

When possible and to the extent feasible, the UNSMS may lend

assistance in a crisis situation for in extremis support. Travel or

nancial assistance will be provided on a space-available and

reimbursable basis. This includes assistance to NGOs covered

under the Saving Lives Together Framework of cooperation

with the United Nations. The DO authorizes the details of this

assistance.

48

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

3

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

INCIDENTS TARGETING PERSONNEL

AND PREMISES

Increasingly, United Nations personnel and premises have been

targeted directly by a range of hostile threat actors resulting in

injuries, fatalities, impact to programmes or damage to United

Nations facilities. Depending on the seriousness of the incident, the

DO may be required to manage a crisis situation, and/or respond to

post-incident reviews including Boards of Inquiry. With respect to

gender-based security incidents, care should be taken to respect

the response and reporting wishes of the affected personnel. The

UNSMS has promulgated a gender manual which provides more

detailed explanations on how to address gender considerations in

security management.

Where perpetrators of direct attacks against the United Nations

have been identied, the DO needs to pursue further with the

relevant host Government oce to ensure appropriate action is

taken, including police investigations and, where applicable, actions

in accordance with the Convention on the Safety and Security of

United Nations and Associated Personnel.

49

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

3

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

UNSMS Board of Inquiry

A Board of Inquiry (BOI) is a mechanism to review

investigation reports and record the facts of critical

security incidents involving organizations of the UNSMS,

including whether the occurrence took place as a result

of the acts or omissions of any individual(s). A BOI is

neither an investigative nor a judicial process and does not

make recommendations on questions of compensation,

legal liability or disciplinary action. The purpose of a BOI

is to identify gaps or deciencies in UNSMS SRM policies,

procedures or operations, to strengthen SRM controls

(lessons learned) and to improve accountability for security

risk management. Pursuant to Security Policy Manual

Chapter V, Section E, a BOI may be convened after the

investigators of the affected organizations have completed

their investigation of the incident in accordance with their

applicable legal framework.

Note: The policy covering a UNSMS BOI is different from

those governing BOIs specically for peacekeeping

missions and special political missions. These are triggered

by specic circumstances, which are primarily concerned

with cases of death, injury or kidnapping involving mission

personnel, or major damage or loss of assets owned

by the mission or involving mission personnel. These

circumstances are outlined in the SOP for such BOIs.

SPECIFIC SECURITY

CONSIDERATIONS

4

51

SPECIFIC SECURITY CONSIDERATIONS

4

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

T

his chapter outlines specic security considerations, including

for those that should be mainstreamed, such as gender, along

with several distinct situations, such as event security and

arrest and detention of personnel.

GENDER AND INCLUSIVITY

United Nations personnel experience different risks. Ensuring that

these diverse risks are included in the SRM is a key responsibility of

the DO and the SMT, as outlined in the Framework of Accountability.

Security operations must be gender-sensitive and gender-responsive

to ensure the safety and security of its entire workforce. The UNSMS

Policy on Gender Inclusion in Security Risk Management outlines

requirements that must be considered at different stages of the SRM

process. The aim is to ensure that specic gender-based threats or

measures are identied and appropriately included in all security

planning.

• All incoming security briengs must include gender-specic

threats, risks and related mitigation measures in the duty

country.

• Residential security measures and contingency plans must

be reviewed to ensure they are gender inclusive.

• The SRM in each country must address gender at each

stage of the process, ensuring appropriate and effective

mitigation measures are identied and implemented.

• All UNSMS personnel must complete the ‘I Know Gender’

training course.

• All locations must develop an aide-memoire providing

guidance to personnel on available resources in the event of

a gender-based security incident.

Applying a gender lens throughout the SRM process is critical to

ensuring that gender perspectives are captured and addressed.

52

DO AND SMT HANDBOOK

4

SPECIFIC SECURITY CONSIDERATIONS

Gender-based security incidents¹, including sexual violence, may

occur against internationally and locally recruited United Nations

personnel in your area of responsibility. In response to these serious

incidents, security personnel are guided by core principles, including,

but not limited to: the identication of, and transfer to, a safe space,

if requested by the affected person; provision of expert medical and

psychosocial services if required; and strict condentiality. This

information should be consolidated by UNDSS and the Security

Cell in the aide-memoire for responding to a gender-based security

incident. Where available, gender experts in-country or regionally

based can be consulted to provide input on specic gender and

security-related risks, hence ensuring that these are appropriately

integrated into the SRM. A Manual on Gender Considerations in

Security Management, published in 2019, offers practical advice for

security professionals.

1 Gender refers to the attributes, opportunities and relationships associated with being

male or female, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans-gender and inter-sex (LGBTI) individuals.

Attitudes to sexuality and the expressions of gender and

sexual orientation vary from one country to another. Some

may be instilled from a political level; others may be based

on traditions, religious, cultural and societal norms. At the

United Nations, human rights apply equally to all people

regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity

and expression and sex characteristics (more commonly

referred to as SOGIESC) in just the same way as they do to

age, race and religion.

53

SPECIFIC SECURITY CONSIDERATIONS

4